Exploring DeepGEMM FP8 kernels

Intro

DeepGEMM is a library of fp8 kernels written by the Deepseek team with fine-grained, 128 block/group scaling. It is one of the best learning resources for efficient, clean fp8 kernels because it provides the best balance between complexity and accessibility. Since I am going to be writing a few different FP8 kernels for the Qwen3-Next inference engine, I wanted to completely understand the FP8 GEMM, and use it as a starting point for writing other fp8 kernels.

I'm going to skip past describing how NVFP8 and quantization work, but I want to briefly mention CuTLASS which is what the DeepGEMM is based out of. CuTLASS has also supported fp8 blockscaled GEMM since version 3.7. However their implementation is fogged up by all the abstractions inside the repository, so DeepGEMM chose to write a simpler kernel with the same structure and some additional optimizations, albeit with much clearer code.

Kernel

I'm going to be looking at this file. This is a straightforward GEMM kernel which implements $Y = XW$ or $C = AB$, where X is the input activation, usually in the shape (batch_size, seq_len, w_in), and the weight vector $W$ with shape (w_out, w_in).

A key difference from non-quantized GEMM is the presence of the scale factor tensors for both inputs, with $A$ being quantized with 1D 128-block scaling dynamically, while the weight vector is quantized with 2D (128, 128) block scaling. Thus if $A$ has shape $(M, K)$, the Scale Factor A (SFA) tensor has shape $(M, \frac K {128})$, and if B has shape $(K, N)$, then SFB tensor has shape $(\frac K {128}, \frac N {128})$. Scales are always fp32.

Prelim: WGMMA's Accumulator Layout

After I read through the file a few times and transcribed it line by line, with additional comments as notes, I found a common shape across the GEMM tiles. Consistently, both the row and column dimensions of the output matrix D were being grouped into sizes of 8, here's a few lines where this happens:

const auto r_0 = warpIdx * 16 + lane_idx / 4, r_1 = r_0 + 8;

...

uint32_t num_former_iters = bN / 8;

uint32_t num_full_iters = num_former_iters;

These lines of code will make more sense later, in the full context of the kernel. The reason behind this seemingly arbitrary grouping tiling of 8 x 8 is because of one PTX instruction:

stmatrix.sync.aligned.shape.num{.trans}{.ss}.type [p], r;

.shape = {.m8n8, .m16n8};

.num = {.x1, .x2, .x4};

.ss = {.shared{::cta}};

.type = {.b16, .b8};

This instruction performs a load from register memory to shared memory across a single warp of threads, thus the sync keyword. The shape keyword describes the tile of elements that is loaded in with options between (8x8, 16x8) matrices, as well as a num variable that determines the number. In the FP8 kernel case, the output matrix has type bf16, because this balances both precision and memory. Thus we set .b16 for the type argument. An example using a bf16 type, from the PTX docs:

// Store four 8x8 matrices

.reg .b64 addr;

.reg .b32 r<4>;

stmatrix.sync.aligned.m8n8.x4.b16 [addr], {r0, r1, r2, r3};

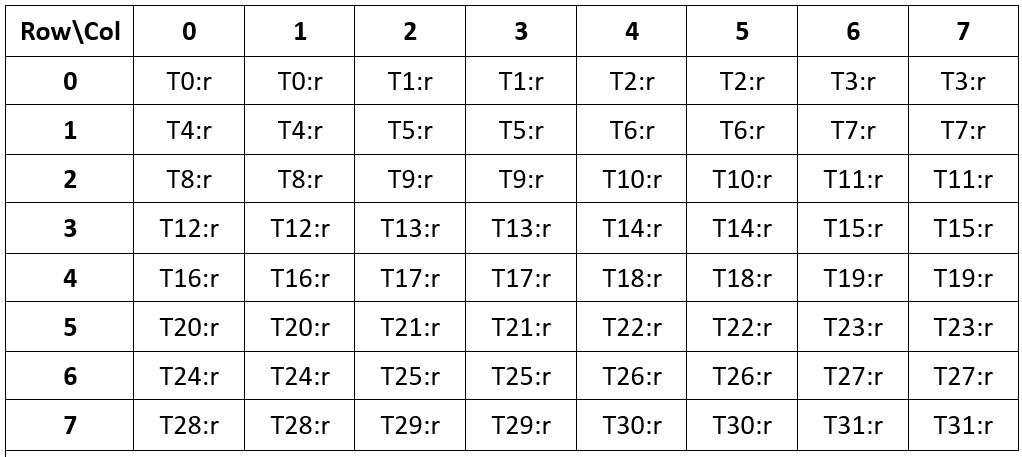

The first argument, addr describes the 32bit / 64bit address of the top left corner of the matrix, and the next four variables are 32 bit that hold the values to be moved. The number of registers equals the number of matrices being loaded in, and since each one is 32bit, it actually holds 2 elements of the matrix. An entire warp fills an 8 x 8 matrix as such:

THus, we want to be aware of this tiling structure across the entire WGMMA problem shape of M x N. CuTLASS code also references this, although without any link to the PTX documentation:

template<int N>

using CLayout_64xN = Layout<Shape <Shape < _4,_8, _4>,Shape < _2,_2,Int<N/8>>>,

Stride<Stride<_128,_1,_16>,Stride<_64,_8, _512>>>;

The C Layout is formatted in the TV_Layout CuTLASS uses throughout the repository - it maps an input (thread_index, value_index) into the matrix shape. If this looks unfamiliar, read through the CuTE Layout section. The first inner mode of the layout comes out to (4,8,4) : (128, 1, 16), and corresponds to how the threads in a warpgroup are layed across a WGMMA tile - see that $4 * 8 * 4 = 128$. The first 4 in the shape corresponds to a stride of 128 elements, and describes the spacing between lanes in different warps.

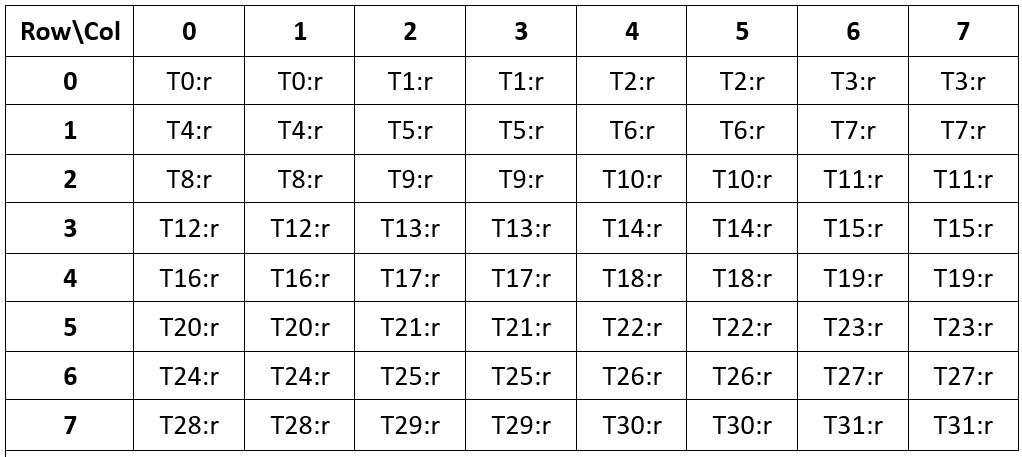

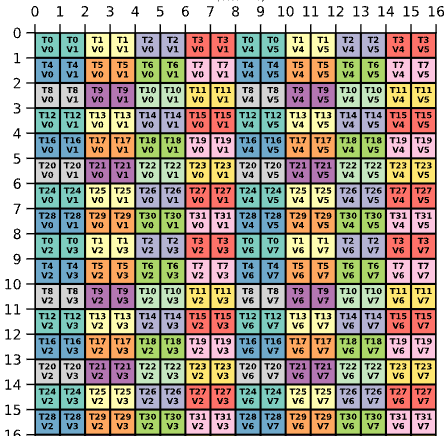

The more interesting shape is: (2,2, N/8) : (64, 8, 512). This describes how the values in a given thread's registers are mapped across the output matrix. A visual always helps, so here's a nice gist by Horace He that quickly graphs TV_Layouts. I just graphed the simple case where $N = 16$, and truncated only the first 16 rows, since this holds an entire warp.

The layout is a column-major layout, following NVIDIA's column-major convention in all their libraries. The M dimension is always fixed to 64 rows for WGMMA instructions, so although the layout is itself column-major, it is mapping the (thread_index, value_index) to a physical row-major lyaout.

The second 'row' of the (2,2) tile is separated 8 rows down, and is again contiguous for the two values. Notice the similarities of the (V0, V1) tile of the warp (T0-T31), and the mapping of the thread registers for the $8 \times 8$ matrix used in stmatrix. They exactly line up.

Similarly, the (V2, V3) values for a warp make up another $8 \times 8$ matrix and so on. We can now look at the last mode in the value layout: $N/8$. As mentioned before, it chunks up the N column into groups of 8, so that in a single 8-column group the a warp of threads maps to the $16 \times 8$ tile exactly. This tile of two $8 \times 8$ stacked on each other is what is used in the x2 version of the stmatrix instruction.

So this explains why we need to ensure that each thread in a WGMMA warpgroup will have its values split across chunks of 8 columns, and inside each 8-column chunk it holds 4 accumulator variables that correspond to the $(2,2)$ grid in the CuTLASS layout.

Kernel Prologues

Lines 33 - 141 in the kernel are mostly setup and establishing a bunch of constexpr that will come up later. I want to speed through these and explain the important ones as well as the ones that don't have an immediately apparent purpose.

Block size checks:

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_K == 128, "Only support per-128-channel FP8 scaling");

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(constexpr_ceil_div(BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K) == 1 or (constexpr_gcd(BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K) == BLOCK_N - BLOCK_K), "Too much B scales in a single block");

The first one immediately checks that the block size for K is 128 in both A and B - the rest of the kernel is based off this assertion, so very important.

The second assertion checks that there aren't too many B scales in the N direction of B. This kernel limits itself to at most two scale factors inside the current $(\mathrm{BLOCK_K}, \mathrm{BLOCK_N})$ tile to avoid more complex cases. Since $bK$ is fixed, the first statement in the or checks if $\mathrm{BLOCK_N} < \mathrm{BLOCK_K}$ using a constexpr ceil div, but it's equivalent. The second condition is when $\mathrm{BLOCK_N} >= \mathrm{BLOCK_K}$, and is just equivalent to asserting $\mathrm{BLOCK_N} <= \mathrm{BLOCK_K} * 2 = 256$

Next, the WGMMA atom fetcher:

using WGMMA = typename FP8MMASelector<BLOCK_N>::type;

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_M % WGMMA::M == 0 or BLOCK_M < WGMMA::M, "Invalid block size");

The first line uses the templated BLOCK_N to get the WGMMA atom that will be used throughout the kernel. The full method and class can be seen in their github. Note that they have a selector struct as well as the actual atom struct FP8MMA that calls into CuTLASS internals. The second assert is used to check the BLOCK_M dimensions are valid for the problem.

Uniform scaling check:

static constexpr bool kMustUseUniformedScaleB = (BLOCK_K % BLOCK_N == 0);

This variable is very important and will come up often in the kernel. It describes whether for a given B tile of shape $(\mathrm{BLOCK_K}, \mathrm{BLOCK_N})$ you will need to load in one or multiple (two) scale factors. Two scale factors would be needed if BLOCK_N = 96, since now each BLOCK_N doesn't fit neatly into BLOCK_K, and there's an overlapping pattern. The first use of the variable is seen on line 74:

// shape_k_scales = ceil_div(K, BLOCK_K)

const uint32_t& smem_sfb_size = align<uint32_t>(shape_k_scales * (kMustUseUniformedScaleB ? 1 : 2) * sizeof(float), sizeof(Barrier));

When BLOCK_N = 96, kMustUseUniformedScaleB = false, and we need to make shared memory have size (shape_k_scales, 2).

Shared Memory Alignment Check:

// Align to 1024 bytes for swizzle-128B

extern __shared__ __align__(1024) uint8_t smem_buffer[];

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(SMEM_D_SIZE % 1024 == 0, "Shared memory of A/B must be aligned to 1024 bytes");

This check asserts that the shared memory tiles of A and B, which I'll refer to as sA and sB from now, are aligned to 1024 bytes. This is because of the GMMA Matrix Descriptor Format Rules. Specifically, the base offset is only 0 for 128B swizzling when the matrix start address in shared memory is aligned to a 1024-byte boundary. The DeepGEMM authors made sure to enforce 128B swizzling for sA and sB throughout the kernel.

Scheduler Initialization:

auto scheduler = Scheduler<kGemmType, BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N, kNumGroups, kNumTMAMulticast, kIsTMAMulticastOnA, kNumSMs>(shape_m, shape_n, shape_k, grouped_layout);

This initializes the Scheduler struct, which is a persistent tile scheduler, and especially important for GroupedGEMM scenarios. I wrote about this struct in a separate post (link here).

The rest of the code until line 152 is some boilerplate, like setting up barriers and shared memory pointers, assigning registers, setting up a lambda function on line 143 that mirrors the CuTLASS PipelineState struct.

The Warpgroups Split

This kernel is warpgroup-specialized, which means that different warpgroups (128 threadgroups) perform different features. In this case, there is one warpgroup assigned to setting off TMA loads from GMEM, and at least one math warpgroup that performs the WGMMA.

TMA Warpgroup

The TMA Warpgroup path is pretty simple - they set up a while loop with the scheduler, which keeps checking if there's another (m_block_idx, n_block_idx) to fetch. It then iterates through the K dimension using software pipelining and then initializes TMA loads for the A, B, and SFA (Scale Factor A) tensors. Two things to note: the SFA tensors load is below:

tma_copy<BLOCK_M, BLOCK_K, 0>(&tensor_map_sfa, &full_barrier,

smem_sfa[stage_idx], m_block_idx * BLOCK_M, scheduler.get_global_idx<kWithGroupOffsetA>(shape_k_scales, 1, k_block_idx),

num_tma_multicast_a);

The tma_copy method can be explored in more detail at this link. When looking at the method signature, you'll notice that the SFA is MN-major - this is intentional since each iteration of the K loop could be using multiple scale factors across the MN dimensions. Also, there is no load for the SFB - it is loaded directly through CUDA functions.

One last thing that I really liked about the TMA section was DeepGEMM's choice to write a thin TMA wrapper. It's not overly complex, but a crucial feature is that the multicast is toggleable, since they directly call CuTLASS's cute::SM90_TMA_LOAD_XD::copy() method instead of using make_copy_atom. This allows them to handle ragged tiles and boundary conditions much more cleanly compared to vanilla CuTLASS, where you would need to pass in multiple TMA atoms to be able to toggle multicast.

Math Warpgroup

This is the meat of the kernel, so it deserves its own section.

Setup

Let's first look at the setup, which involves creating the GMMA Descriptor, described in the PTX docs.

auto a_desc = make_smem_desc(smem_a[0] + math_wg_idx * WGMMA::M * BLOCK_K, 1);

auto b_desc = make_smem_desc(smem_b[0], 1);

The helper function make_smem_desc is just a short function that assigns bits according to the Matrix Descriptor Format. WGMMA::M here is just the M dimension size of the WGMMA atom, which is always set to M = 64. math_wg_idx is the warpgroup idx the thread belongs to, so we shift the sA down by one tile.

template <class PointerType>

CUTE_DEVICE cute::GmmaDescriptor make_smem_desc(PointerType smem_ptr, const int &layout_type, const int &LBO = 0,

const int &SBO = 1024) {

cute::GmmaDescriptor desc;

uintptr_t base_address = static_cast<uint32_t>(__cvta_generic_to_shared(smem_ptr));

desc.bitfield.start_address_ = (base_address & 0x3ffff) >> 4;

desc.bitfield.layout_type_ = 1; // always 128B swizzle

desc.bitfield.leading_byte_offset_ = LBO >> 4;

desc.bitfield.stride_byte_offset_ = SBO >> 4;

desc.bitfield.base_offset_ = 0; // from shared memory alignment

// matrix-descriptor-encode, from the docs takes the last 18 bytes, then

// shifts down by 4 to create the 14 bits

return desc;

}

const uint32_t a_desc_lo = __shfl_sync(0xffffffff, a_desc.reg32_[0], 0);

const uint32_t b_desc_lo = __shfl_sync(0xffffffff, b_desc.reg32_[0], 0);

At first, this line seems useless, since every thread already fetches a_desc. Apparently, doing this __shfl_sync no-op actually tells nvcc that a_desc_lo should be stored in an unified register, which are special registers that are shared by all the threads in a warp. This is an important optimization in kernels that creep to the physical register limit per thread, since it provides a 32x reduction. The a_desc_lo variable is also important - when examining the bitfield of the descriptor, it is the lower 32 bits of the 64 bit descriptor, which contains the SMEM address. This pointer will be moved around a lot throughout the loops.

Next, we start the persistent scheduler while loop and load in the b-scales. Another important variable, num_former_iters is introduced here:

uint32_t num_former_iters = BLOCK_N / 8, num_full_iters = num_former_iters;

if constexpr (not kMustUseUniformedScaleB) {

num_former_iters = min(BLOCK_N, BLOCK_K - n_block_idx * BLOCK_N % BLOCK_K) / 8;

num_full_iters = min(shape_n - n_block_idx * BLOCK_N, BLOCK_N) / 8;

}

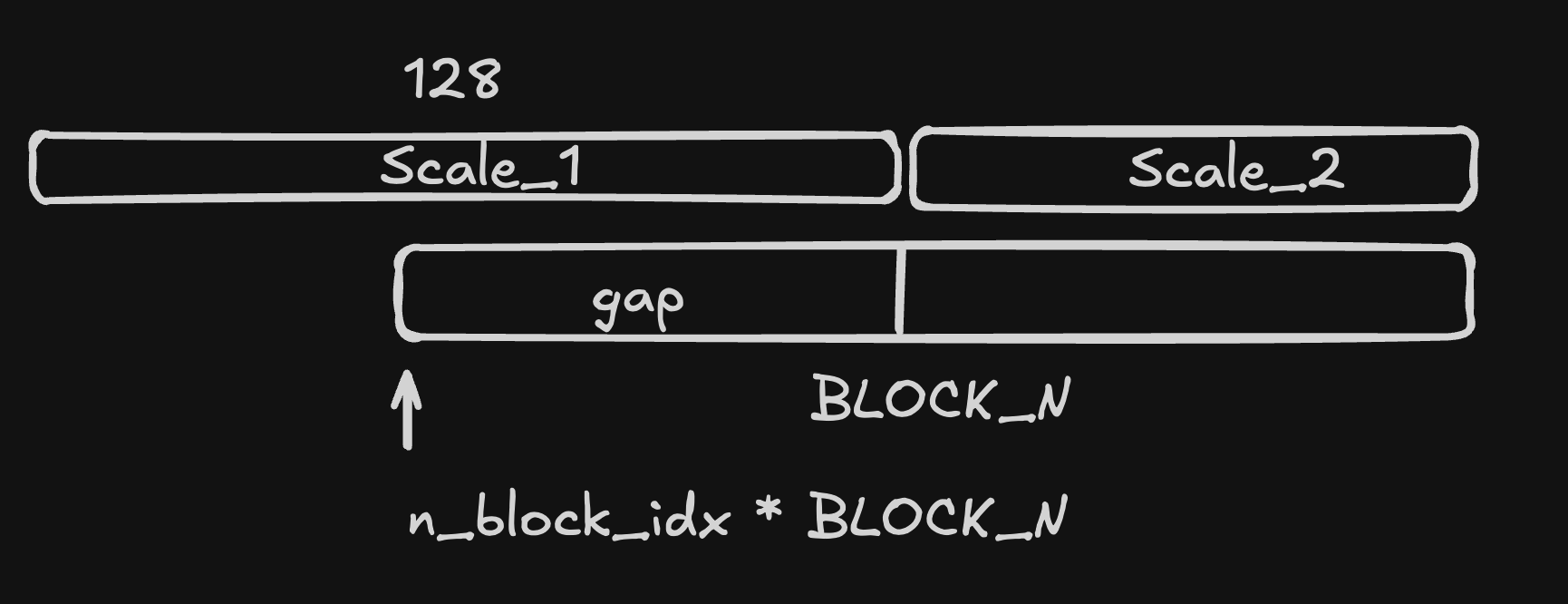

uint32_t num_sfb = shape_k_scales * (num_former_iters >= num_full_iters ? 1 : 2);

Notice the condition - recall this is what determines if it possible to have multiple B scale factors in a block. If this is true, we still need to determine whether the current B block needs one or two. Notice that both iters are in units of 8 columns, mirroring what was said in the Prologoue about the (8, 8) tile units. Let's go into the if-loop. Here, num_former_iters describes the remaining 8-column chunks from the previous scale factor, while num_full_iters describes the number of 8-column chunks left in the entire BLOCK_N tile. When num_former_iters < num_full_iters, that means there needs to be another scale to fill that gap, i.e two scales.

After determining the number, the B scales are loaded. One small note here is that the first warp doesn't participate in loading B-scales, since it is assigned to calling TMA stores from SMEM to GMEM for the output - this will be shown at the end of one iteration of the Math warpgroups.

M Dimension Wave Blocks

DeepGEMM chooses to create a WAVE_BLOCK_M variable that further chunks up the BLOCK_M dimension when BLOCK_M > WGMMA::M:

constexpr uint32_t WAVE_BLOCK_M = BLOCK_M <= WGMMA::M ? BLOCK_M : WGMMA::M * 2;

// enforces BLOCK_M be a nice multiple of 128 / 64

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_M % WAVE_BLOCK_M == 0, "Invalid block sizes");

// Pick threads whose WGMMA results are to be stored in shared memory

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_M >= 64 or kNumMathThreads == 128, "Only one math warp group for `BLOCK_M < 64`");

constexpr uint32_t kNumWGMMAStoreThreads = WAVE_BLOCK_M * (128 / WGMMA::M);

const bool do_wgmma_store = BLOCK_M >= WGMMA::M or warp_idx < kNumWGMMAStoreThreads / 32;

The variable's purpose is more obvious when BLOCK_M is much larger than WGMMA::M, for example if BLOCK_M = 256, and WGMMA::M is always 64. In this case, the WAVE_BLOCK_M is set to twice the WGMMA atom dimension, and will use two warpgroups per wave. This two warpgroup limit is also an implicit limit not mentioned in the kernel.

The WAVE_BLOCK_M variable also influences the constexpr kNumWGMMAStoreThreads variable, which is used as a predicator for a given thread's WGMMA output. That's why for the BLOCK_M >= WGMMA::M case, all threads will participate since the BLOCK_M is large enough - when it is smaller the number of store threads is a fraction of the warpgroup's 128 threads, and we gate by warp index.

Cool Compiler Trick

// The compiler must know the dynamic variable `num_former_iters`'s real value

constexpr bool kShouldOptimize = BLOCK_K / constexpr_gcd(BLOCK_K, BLOCK_N) <= 4 and not kMustUseUniformedScaleB;

constexpr uint32_t kGap = constexpr_gcd(BLOCK_K, BLOCK_N) / 8;

constexpr uint32_t kEnd = kShouldOptimize ? BLOCK_K / 8 : 0;

// Dispatch `num_former_iters` and launch MMAs

dispatch_num_former_iters<0, kGap, kEnd>(kShouldOptimize ? num_former_iters : 0, [&](auto _) { // ...

When I first saw this section of the code, I was extremely confused. This is right before the start of the blocked K loop that performed the WGMMA, but I could not understand what the purpose of the dispatch_num_former_iters method was or the inputs it took. After some back and forth with ChatGPT I found the reason and it is pretty elegant. Like the comment says, num_former_iters is a dynamic, runtime variable that the compiler doesn't know, which prevents potential compiler optimizations. We want to find a way to statically determine this variable, when possible.

This is where the dispatch_num_former_iters method comes in:

template <uint32_t kNumFormerIters, uint32_t kGap, uint32_t kEnd, typename func_t>

__device__ void dispatch_num_former_iters(uint32_t num_former_iters, const func_t& func) {

if (num_former_iters == kNumFormerIters) {

func(cute::Int<kNumFormerIters>{});

return;

}

if constexpr (kNumFormerIters + kGap <= kEnd)

dispatch_num_former_iters<kNumFormerIters + kGap, kGap, kEnd>(num_former_iters, func);

}

During compile-time, it will perform a linear search, starting from the initial value of kNumFormerIters, and adding values of kGap until it finds the dynamic variable num_former_iters, or it reaches the end of the possible values. If it find the value, it then calls the lambda func passed in, which in our case is the WGMMA logic. Another way to write this, without templates is:

while (kNumFormerIters != num_former_iters && kNumFormerIters + kGap <= kEnd) {

kNumFormerIters += kGap;

}

if (kNumFormerIters < kEnd) func(kNumFormerIters)

In order to understand the three variables kShouldOptimize, kGap, kEnd, we now need to use a little number theory. We are only concerned with num_former_iters when there can be more than one B scale in a block. This happens when the boundary of a scale factor is in the middle of a B block:

If kShouldOptimize IS true, then the search is performed, and here the kGap variable is how much the gap increases per iteration of the cycle. This can again be seen by looking at the relation $\mathrm{gap} = g * nB (bN \mod bK)$ - all variables are fixed beside the block idx $nB$, so incrementing the cycle increments the gap in intervals of the GCD. The kEnd variable describes the end of the scale range, and notice that both kGap and kEnd are again in units of $N/8$, persisting the 8-column chunks.

Computation Loop

We can now begin the actual K-tiled loop for WGMMA. This loop has a two loop structure:

// basic k tile loop

for (int k_block_idx = 0; k_block_idx < num_total_k_blocks; advance_pipeline(k_block_idx))

// loop across the M block waves

for (uint32_t local_idx = 0; local_idx < BLOCK_M / WAVE_BLOCK_M; ++ local_idx)

// wgmma logic

The outer loop is not that interesting - it moves the shared memory addresses according to the current stage / pipeline state, and loads the current B and A scales, ensuring the appropriate ones are loaded to match the 2 x 2 grid described in the Prelim section. The inner loop contains several interesting parts, beginning with the kNumAccum. This is a variable from the WGMMA atom, kNumAccum = WGMMA::M * WGMMA::N / 128. It describes the number of accumulator registers each thread in a warpgroup requires for a WGMMA, and WGMMA::M = 64 is a constant, so kNumAccum = 64 * WGMMA::N / 128 = WGMMA::N / 2.

Then, the actual WGMMA operation is performed:

#pragma unroll

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < WGMMA::kNumAccum; ++ i)

warpgroup_fence_operand(accum[i]);

warpgroup_arrive();

#pragma unroll

for (uint32_t k = 0; k < BLOCK_K / WGMMA::K; ++ k) {

a_desc.reg32_[0] = a_desc_base_lo + (m_offset * BLOCK_K + k * WGMMA::K) / 16;

b_desc.reg32_[0] = b_desc_base_lo + k * WGMMA::K / 16;

WGMMA::wgmma(a_desc, b_desc, accum, k);

}

warpgroup_commit_batch();

#pragma unroll

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < WGMMA::kNumAccum; ++ i)

warpgroup_fence_operand(accum[i]);

warpgroup_wait<0>();

These functions are all CuTLASS helpers that wrap PTX instructins - the first unrolled loop prepares the accumulator registers with a memory fence to ensure ordering of reads and writes. The next loop performs a loop over the BLOCK_K dimension in chunks of the K size of the WGMMA operation, advancing the base shared memory address of the matrix descriptor appropriately. The last unrolled loop is cleanup.

We then come to the promotion logic - manual promotion per WAVE_BLOCK_M size of WGMMA is necessary. The DeepGEMM authors realized that the FP8 tensor cores used an accumulation strategy that used only 14 bits of precision instead of the 32 bits of FP32 - this led to writing this manual promotion:

float scale_0_0 = scale_a_0 * scale_b_0, scale_1_0 = scale_a_1 * scale_b_0;

float scale_0_1, scale_1_1;

if constexpr (not kMustUseUniformedScaleB)

scale_0_1 = scale_a_0 * scale_b_1, scale_1_1 = scale_a_1 * scale_b_1;

auto shifted_accum = final_accum + WGMMA::kNumAccum * local_idx;

#pragma unroll

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < WGMMA::kNumAccum / 4; ++ i) {

// NOTES: for unrolled `num_former_iters` cases, we expect the compiler to automatically make it a constant

const bool& predicate = kMustUseUniformedScaleB or i < num_former_iters;

shifted_accum[i * 4 + 0] += (predicate ? scale_0_0 : scale_0_1) * accum[i * 4 + 0];

shifted_accum[i * 4 + 1] += (predicate ? scale_0_0 : scale_0_1) * accum[i * 4 + 1];

shifted_accum[i * 4 + 2] += (predicate ? scale_1_0 : scale_1_1) * accum[i * 4 + 2];

shifted_accum[i * 4 + 3] += (predicate ? scale_1_0 : scale_1_1) * accum[i * 4 + 3];

}

This promotion code makes more sense when looking at the layout that it is following, the 8 x 8 matrices from the stmatrix PTX instruction:

Remember that for the (x2) instruction DeepGEMM uses, there is another 8 x 8 matrix stacked below this one, with the same format copied down. The first three lines create the composite scales. Each thread is always writing to two distinct rows in the 16 x 8 output, so we make sure to have two scales, scale_0_0, scale_1_0. We also cover the case where two scales may be needed in the column direction, depending on which 8-column chunk we are using, by loading in another two-row column of scales.

The last unrolled loop is the actual promotion loop, where we multiply-add the scale factors of the output matrix with the FP32 values in the accum register. The predicate variable is used to determine whether to use the second column of scale factors, depending on which 8-column chunk we are in. Note that kNumAccum / 4 = (N / 2) / 4, so the loop variable serves a dual purpose as a iterator over 8-column chunks and 4 WGMMA accumulator variables.

TMA Stores

This is the final stage of the kernel, where we finally use the stmatrix instruction to load the register values into shared memory. Since we are using a TMA store instruction from SMEM to GMEM, and stmatrix is a direct data transfer, we need to manually write the swizzling logic ourselves.

Here are some important checks and variables:

constexpr uint32_t kNumElemBytes = sizeof(nv_bfloat16);

constexpr uint32_t TMA_D_BLOCK_N = kSwizzleDMode == 0 ? BLOCK_N : (kSwizzleDMode / kNumElemBytes);

constexpr uint32_t WGMMA_M_PER_WARP = WGMMA::M / 4;

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_M % 8 == 0, "Invalid swizzling atom");

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(BLOCK_N % TMA_D_BLOCK_N == 0 and BLOCK_N / TMA_D_BLOCK_N <= 32,

"Unaligned TMA store or too many TMA store instructions");

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(TMA_D_BLOCK_N % 8 == 0, "Invalid TMA block N");

TMA_D_BLOCK_N is the width of the swizzle atom in output elements, or without swizzling it is the entire block.

The first assertion checks that the number of SMEM rows is a multiple of 8 - this is required by the PTX Shared Memory Matrix Layout, where a K-major atom is always 8 rows.

The second assertion checks when swizzling that the swizzle size in elements evenly divides the SMEM column size, and also that the number of swizzle atoms across a column is less than the warp size, because only the first warp will carry out TMA store instructions.

The third assertion checks we can divide the number of elements by 8, from the 8 column requirement of stmatrix instructions.

Here's the entire double looped code of the swizzle calculation + SMEM store, we care mostly about the code block in the inner most loop:

DG_STATIC_ASSERT(WGMMA::kNumAccum % 4 == 0, "Invalid STSM x2 vectorization");

#pragma unroll

for (uint32_t local_idx = 0; local_idx < BLOCK_M / WAVE_BLOCK_M; ++ local_idx) {

auto m_offset = local_idx * WAVE_BLOCK_M;

auto shifted_accum = final_accum + WGMMA::kNumAccum * local_idx;

#pragma unroll

for (auto i = 0; i < WGMMA::kNumAccum / 4; ++ i) {

// Swizzle or padding into the correct address

uint8_t* smem_ptr = nullptr;

if constexpr (kSwizzleDMode > 0) {

// Calculate the swizzling atom offset and in-atom offset

constexpr uint32_t kNumBankGroupBytes = 16;

auto atom_offset = i / (TMA_D_BLOCK_N / 8), in_atom_offset = i % (TMA_D_BLOCK_N / 8);

// Calculate the index of the bank group to be written in the atom

auto bank_group_index = in_atom_offset + lane_idx * (kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes);

// Reshape the atom in another view and swizzle

// - original: `(BLOCK_M, kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes)`

// - new: `(BLOCK_M * kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes / 8, 8)`

constexpr bool kHasShortcut = (kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes) == 8;

auto row = kHasShortcut ? (in_atom_offset / 8 + lane_idx) : (bank_group_index / 8);

auto col = kHasShortcut ? (in_atom_offset) : (bank_group_index % 8);

col ^= row % (kSwizzleDMode / 16);

// Add back into the base pointer

// NOTES: think twice before modifying this, as changes may affect the number of instructions

smem_ptr = reinterpret_cast<uint8_t*>(smem_d) + // Base pointer

warp_idx * (WGMMA_M_PER_WARP * kSwizzleDMode) + // Warp offset

m_offset * kSwizzleDMode + // Wave offset

atom_offset * BLOCK_M * kSwizzleDMode + // Swizzle atom offset (constants)

row * (kNumBankGroupBytes * 8) + col * kNumBankGroupBytes; // In-atom offset

} else {

// No swizzling, just padding

smem_ptr = reinterpret_cast<uint8_t*>(smem_d + (m_offset + warp_idx * WGMMA_M_PER_WARP + lane_idx) * BLOCK_N + i * 8);

}

// NOTES: only 16 lanes' addresses are used

SM90_U32x2_STSM_N<nv_bfloat162>::copy(

__float22bfloat162_rn({shifted_accum[i * 4 + 0], shifted_accum[i * 4 + 1]}),

__float22bfloat162_rn({shifted_accum[i * 4 + 2], shifted_accum[i * 4 + 3]}),

smem_ptr

);

}

}

Swizzle Logic (Inner Loop)

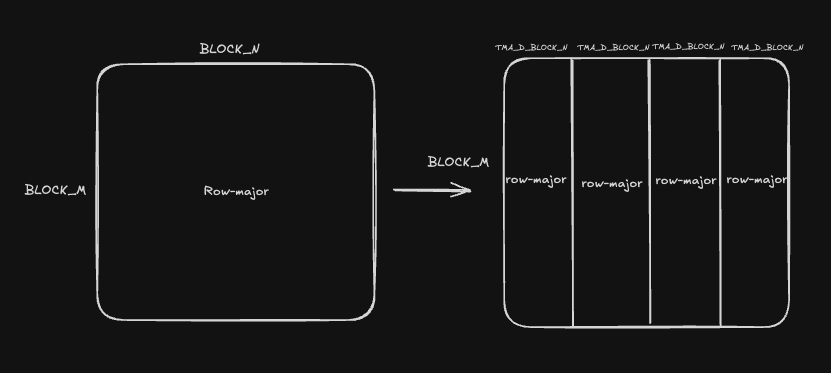

To preface, the goal of this code block is to take the convert the row-major SMEM output matrix of shape (BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N) into shape (BLOCK_N / TMA_D_BLOCK_N, BLOCK_M, TMA_D_BLOCK_N), which fits the TMA store shape. A diagram may be more straightforward:

I'm going to dissect the code block chunk by chunk, starting with the offset calculations. The non-swizzle case is straightforward.

// Calculate the swizzling atom offset and in-atom offset

constexpr uint32_t kNumBankGroupBytes = 16;

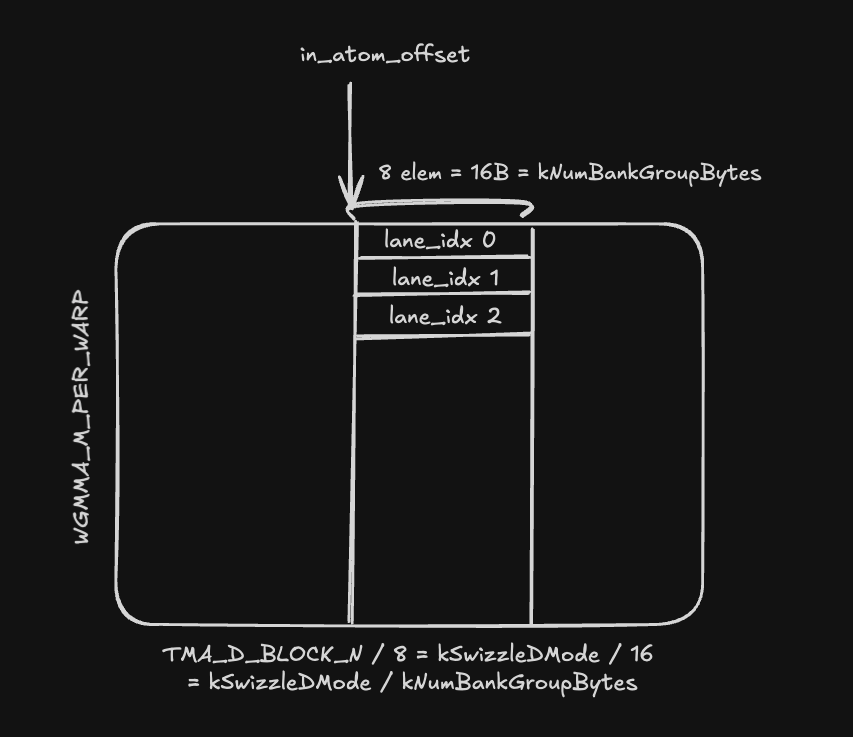

auto atom_offset = i / (TMA_D_BLOCK_N / 8), in_atom_offset = i % (TMA_D_BLOCK_N / 8);

// Calculate the index of the bank group to be written in the atom

auto bank_group_index = in_atom_offset + lane_idx * (kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes);

The kNumBankGroupBytes variable represents the units of the swizzled shared memory pointer, since this matches the column width of the stmatrix in bytes - 8 x size(bf16) = 16. Another interpretation, which Gemini told me is that is the size of bank group. A bank group, which is four shared memory bank (4 * 4B = 16B) is a common hardware access width.

We then calculate the atom_offset and in_atom_offset - these are also calculated in units of 8-column chunks once again. The atom offset will be used to determine which TMA_D_BLOCK_N size column to place in.

We then use the bank_group_index to calculate the write addresses of the stmatrix instruction. This is a linearized index of the below row-major layout, where everything is in units of per 8-output values. Here, the in_atom_offset describes the column index, which advances each iteration of the inner loop. The lane_idx corresponds to the row index of the swizzle atom, which is also chunked by 16 B, or 8-values. Thus the units line up, of per 16 B or 8 values.

So now each of our bank group indices correspond to the linearized index of a (row, col) pair in the atom of shape (WGMMA_M_PER_WARP = 16, kSwizzleMode / kNumBankGroupBytes). More specifically, it is a single column of this atom where we will issue the stmatrix load.

We now perform the swizzling operation:

// Reshape the atom in another view and swizzle

// - original: `(BLOCK_M, kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes)`

// - new: `(BLOCK_M * kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes / 8, 8)`

constexpr bool kHasShortcut = (kSwizzleDMode / kNumBankGroupBytes) == 8;

auto row = kHasShortcut ? (in_atom_offset / 8 + lane_idx) : (bank_group_index / 8);

auto col = kHasShortcut ? (in_atom_offset) : (bank_group_index % 8);

col ^= row % (kSwizzleDMode / 16);

We now need to slightly reshape the atom, but we aren't going to reorder any of the data. We want to repack the contiguous data so that a single row is 128 bytes, or 8 x 16 B. This is because TMA instructions read 128B (all 32 banks) of shared memory per cycle. This means that for 16,32,64B swizzling we pack multiple rows into a 128 B line, which is why the linearized bank group index was required.

We then perform the swizzling operation, which is the straightforward XOR operation, using the row cycle index as the XOR key. The swizzle operation is bijective and ensures minimal bank conflicts - for a more in depth explanation, Lei Mao's Blog is great. You'll notice that the swizzling operation is being carried out on units of 16B - this is also important since PTX performs the swizzling operation in units of 128 bits or 16 bytes.

Finally, we calculate the swizzled shared memory pointer and issue the stmatrix(x2) instruction:

smem_ptr = reinterpret_cast<uint8_t*>(smem_d) + // Base pointer

warp_idx * (WGMMA_M_PER_WARP * kSwizzleDMode) + // Warp offset

m_offset * kSwizzleDMode + // Wave offset

atom_offset * BLOCK_M * kSwizzleDMode + // Swizzle atom offset (constants)

row * (kNumBankGroupBytes * 8) + col * kNumBankGroupBytes; // In-atom offset

// NOTES: only 16 lanes' addresses are used

SM90_U32x2_STSM_N<nv_bfloat162>::copy(

__float22bfloat162_rn({shifted_accum[i * 4 + 0], shifted_accum[i * 4 + 1]}),

__float22bfloat162_rn({shifted_accum[i * 4 + 2], shifted_accum[i * 4 + 3]}),

smem_ptr

);

Remember that in the new swizzled layout, the matrix is sliced into columns of width kSwizzleDMode bytes and each column represents an atom, so the swizzle atom offset is actually the largest stride.

The warp offset and wave offset just move the pointer down the rows of the atom, and then we use the calculated row and column indices to find the atom offset inside. Note that we cast smem_d to uint8_t, i.e to byte units, so all the other offsets must also be in bytes.

We then perform the stmatrix instruction using a small wrapper, remembering to convert the registers from float to bf16.

The last section of the code carries out the actual TMA store instruction, but this is straightforward and doesn't contain any new content.